Engineering for poultry buildings

Follow these recommendations to help prevent costly losses.

Nationwide has been insuring agriculture since 1909 and maintains an extensive database of losses, including causes when they are identifiable. This database enables us to identify trends and offer insights to members to help prevent losses, including poultry buildings losses due to construction issues.

Here are the three main causes of losses to poultry buildings based on construction and ways poultry producers can help prevent these costly losses.

Engineered building design

Ideally, the structural building system should be fully designed by a licensed engineer or a building kit should be furnished from a manufacturer with an in-house engineering staff. Fully engineered buildings are less susceptible to loss since codified loading criteria are applied to every structural component and each component is then sized to meet minimum structural performance levels. Be wary of partially engineered and non-engineered buildings. Partially engineered buildings are exceedingly common in the poultry industry and are defined as a building where some individual components are engineered, but the structural system as a whole has not. Nationwide’s poultry building loss history has shown that partially engineered buildings are susceptible to failures at the interface where engineered components interact with non-engineered components.

A common example of partially engineered construction: Wood trusses are often engineered components and an engineer-stamped drawing can be (and often is) furnished as evidence of design compliance. Roof purlins (purlins are the structural element that spans truss-to-truss across the top of the truss chord) attach directly to the top chord of wood trusses and are not part of the engineered truss design. All too frequently, the truss-to-purlin connection is undersized, resulting in a loss of the roof during even a modest wind event.

Wood trusses

Examinations after roof collapses on poultry buildings reveal that wood trusses are frequently installed incorrectly. More specifically, the permanent lateral restraint mechanisms for the wood trusses are often missing rows of continuous lateral restraint and/or missing bracing elements.

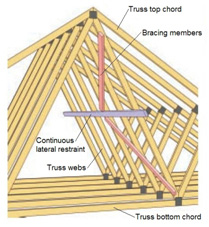

Wood trusses are a collection of chords and webs (see Figure 1). Chords and webs can be stressed in either tension or compression, depending on the loading condition. To prevent premature buckling failures, the slender webs and chords stressed in compression must be continually laterally restrained and braced to rigid building components. When the slender compression members are not correctly restrained and braced, they can fail under loading conditions far less than assumed in the original design.

Figure 1

Because this particular oversight is so common, poultry operators should consider hiring a licensed engineer to perform an inspection of the as-built condition of the permanent lateral restraint mechanisms.

Excessive snow accumulation

Based on our loss history, there is seldom excess load capacity in trusses supplied for agricultural projects. Poultry producers should avoid making any building alterations that could produce additional accumulations of snow on roofs, such as building on additions with differing roof heights or installing snow guards on the roof sheathing. Also, Nationwide suggests producers inspect for snow drifts that form a “ramp” from the ground to the eave of the building roof. These “ramps” can allow wind to impart large unbalanced snow loads to the roof. If these ramps form, farmers should remove the drift.

Nationwide suggests poultry producers in areas of the country that experience significant snowfall prepare a contingency plan to remove snow from the roof after a severe snow event. One of the safest ways to remove snow may be to install multiple knock-out panels in the building’s ceiling liner to allow heated air into the attic space. This can help melt snow accumulation from the roof.

Fire spread prevention

Trends in the poultry industry have lead to larger and larger buildings to house flocks. These super-sized buildings create a significant concentration of value where a fire loss could devastate the future viability of a poultry operation. Although poultry producers likely have insurance to protect against the loss of property and birds, there is no insurance available that protects a producer’s reputation with its partner integrator should a flock be destroyed by fire.

Nationwide suggests using fire divisions within poultry buildings and adequate separation to adjacent buildings to limit the concentration of value and reduce the severity of loss should a fire occur.

Spaces within or connected to the building that create an increased risk to fire (i.e. electrical generator rooms, hot water pressure washer rooms, maintenance shops, break rooms with cooking appliances) should be separated from the poultry confinement area by isolating these rooms with two-hour fire-rated construction. Also consider installing optical smoke detectors specifically designed for use in dusty atmospheres within these spaces to provide an alert to an incipient fire condition.

Adjacent buildings connected by continuous construction or a common corridor should integrate a two-hour rated-fire wall into the construction to prevent fire spread to the adjacent buildings. In conjunction, consider using parapets and fender walls to prevent the fire from short-circuiting across the fire wall (parapets are wall projections that extend above the roof surface and similarly, fender walls are wall projections which extend beyond the wall surface). See Figure 2.

Figure 2

Poultry buildings have traditionally been spaced 40’ to 50’ from neighboring buildings. As the size of poultry buildings continues to increase, this separation distance may no longer be adequate to ensure that neighboring buildings will not become involved in a fire event. The National Fire Protection Agency publication, NFPA 80A: Recommended Practice for Protection of Buildings from Exterior Fire Exposures codifies building separation as a product of building height, width, and the combustibility of the construction materials. As building height and width increase, a corresponding increase in codified building separation is required. Building separation as calculated utilizing NFPA 80A reveals that a typical poultry building of dimensions 50’ wide x 500’ long with 7’ sidewalls and a 5/12 roof pitch should have a minimum building separation of 75’.

Building and equipment maintenance

All building materials and equipment deteriorate over time. Given the caustic nature of the atmosphere within poultry buildings, life expectancy can be quite short. Many poultry building operators use a run-to-failure approach, i.e. materials and equipment are only serviced or replaced following a failure. Nationwide’s claims history reveals a problem with this approach – serious collateral damage can occur following equipment failure. Consider this example based on an actual claim experience: A bearing on a fan shaft fails, causing sparking as the spinning shaft contacts the bearing race. A near-by dust layer of feathers and dander is ignited by the sparking and eventually spreads fire to the adjacent combustible building components. The flock and building are totally destroyed.

Building operators should be vigilant with building and preventive maintenance. Nationwide suggests poultry producers review equipment manuals and develop a spreadsheet to track maintenance activity and frequency. Producers should consult with building contractors and trade professionals to determine inspection activities and timelines for building materials and components.

At a minimum, producers should consider including the following in a preventive maintenance plan:

- Heating appliances to include forced air, radiant, and brooder heaters

- Fuel gas systems

- Electrical components

- Ventilation fans

- Feed motors

- Fire extinguishers

- Wall & roof sheathing

- Sheathing fasteners

- Metal plate truss connectors

Loss information provided in this article is based on data available to Nationwide from 2012 through 2014 for losses in Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

>

>

>

>

>

>